Microservices architecture has gained a lot of popularity recently, with many organizations adopting it to build large and complex applications. One of the biggest challenges in a microservices architecture is managing transactions that span multiple services.

In this blog post, we will explore the concepts of distributed transactions and sagas and how they can be used to manage transactions in a microservices architecture.

Introduction

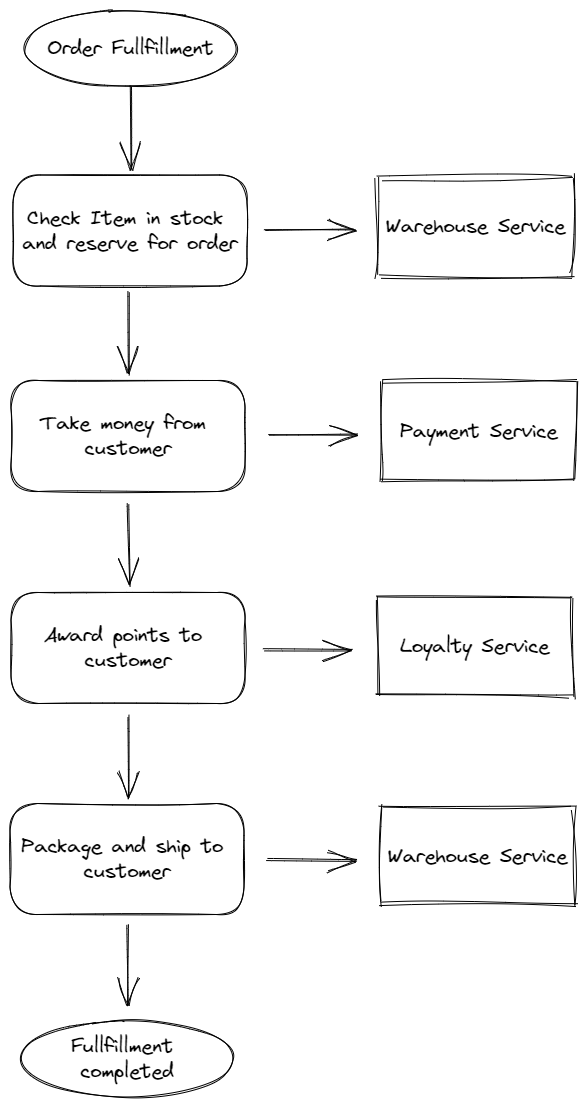

Generally speaking, it is very common to see that multiple microservices are needed together to implement some business logic. For example, the image below inllustrates an example that how an online shopping application implements the “Order Fullfillment workflow” with multiple microservices. As you may know, each step depends on the success execution of previous step.

Now, the question comes to what do we do if one thing goes wrong in this entire workflow and how can we mitigate the impact of the workflow failure? You might heard of a concept in Software Engineering called “Transactions”.

Transactions in this context has the meaning or implies that, serveral actions or requests are binded together to be treated as one single unit. Each action in this overall unit executes successfully, then the “single unit” is treated as running successfully. However, if any step failed, then the whole unit is marked as failed. Since it failed then we might need to clean up some stale resources - Compensation, which we will cover later.

We can utilize database transactions to ensure that the series of changes could be made successfully. Let’s start with what is ACID Transactions and transactions involved multiple tables.

ACID Transactions

ACID transactions refer to a set of properties that ensure reliable and consistent data transactions.

| Property | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Atomicity | Each statement in a transaction (to read, write, update or delete data) is treated as a single unit. Either the entire statement is executed, or none of it is executed. This property prevents data loss and corruption from occurring if, for example, if your streaming data source fails mid-stream. |

| Consistency | Ensures that transactions only make changes to tables in predefined, predictable ways. Transactional consistency ensures that corruption or errors in your data do not create unintended consequences for the integrity of your table. |

| Isolation | When multiple users are reading and writing from the same table all at once, isolation of their transactions ensures that the concurrent transactions don’t interfere with or affect one another. Each request can occur as though they were occurring one by one, even though they’re actually occurring simultaneously. |

| Durability | Ensures that changes to your data made by successfully executed transactions will be saved, even in the event of system failure. |

With the above restrictions, things work pretty well with a single database or single table, collection, etc.. But what about there are two tables that are involved in the action?

ACID without Atomicity

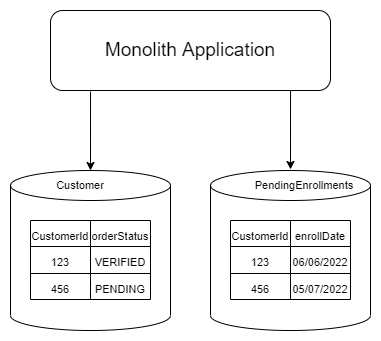

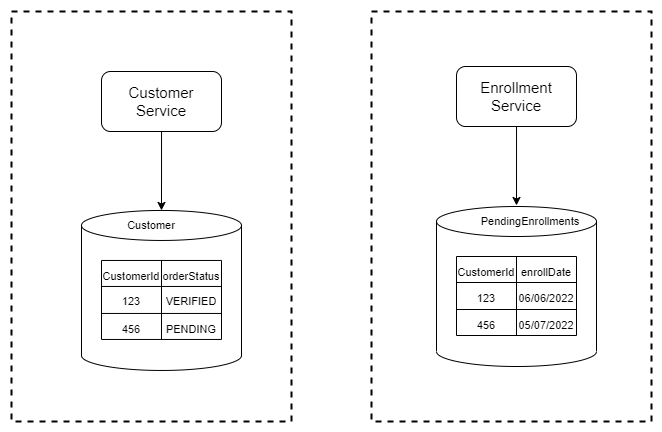

Take the following image as an example: when the customer of customerId=123 has been verified, then the corresponding row in Customer table will update the Status column from PENDING to VERIFIED. Meanwhile customerId=123 in PendingEnrollments table should be removed since the customer is already verified.

When this operation is done in one “boundary” which is a single database, it is easily achievable. However, when it comes to the case that responsibilities are seperated. It actually becomes to a tricky question.

- What if we already updated in

Customertable but the request to delete record inEnrollmenttable failed ? - What if we already removed the record in

Enrollmenttable but the update request toCustomertimed out because of some database issues ?

Distributed Transactions

As we mentioned above, Distributed Transactions may leave us inconsistent data, so let’s see one of the most common algorithms for implementing distributed transactions

Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

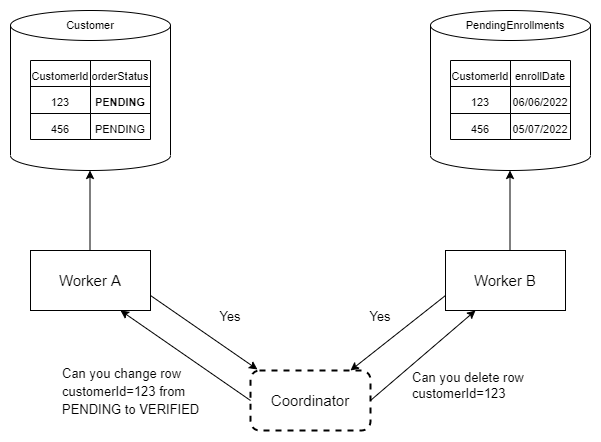

The Two-Phase Commit (2PC) protocol is a classic solution for implementing distributed transactions. In the 2PC protocol, there is a coordinator and multiple participants. The coordinator initiates the transaction and asks each participant to prepare for commit. The participants perform their operations and respond to the coordinator with either a vote to commit or a vote to abort. If all participants vote to commit, the coordinator sends a commit message to all participants. Otherwise, the coordinator sends an abort message to all participants.

This article, Distributed Transactions & Two-phase Commit explains what is Two-Phase Commit pretty well. In summary, 2PC is broken down into two phases:

- Voting Phase

- Coordinator contacts all the workers to ask if any workers will be included in the transactions and get the confirmation

- Commit Phase

- A rollback message will be sent if any worker does not vote for the commit, so anything left could be cleaned up

Another good point mentioned in the book: O’Reilly - Building Microservices, 2nd Edition (Chapter 6: Workflow) regarding the communication of Coordinator and Worker is that:

If the latency between Cordinator and participated workers increases, the worker will process the request more slowly. Then we will observe the intermediate state during the transaction with some probability. This violates the “Isolation” property from ACID.

The 2PC protocol is simple and easy to understand. However, it has some drawbacks:

It is a blocking protocol. The coordinator must wait for all participants to respond before making a decision. If a participant fails to respond, the coordinator cannot make a decision and the transaction is blocked. It is vulnerable to a single point of failure. If the coordinator fails, the transaction cannot proceed. It does not scale well. As the number of participants increases, the likelihood of a failure also increases.

So the main take away for learning the 2PC algorithm is that:

- 2PC will inject a large amount of latency to your system, since each worker will have to apply a Lock to your database table to perform any operations

- The longer the operation takes, the higher probabilty you will see intermediate state

So, genrally, dont use this algorithm

Sagas

A Saga is a pattern for coordinating a distributed transaction that involves multiple services. It allows us to break down the transaction into smaller steps that can be completed independently by each service. If a step fails, the Saga can execute compensating actions to undo the effects of the previous steps.

Orchestrated Saga

In an Orchestrated Saga, there is a central orchestrator that controls the flow of the transaction. The orchestrator sends commands to each service and tracks the status of the transaction. If a step fails, the orchestrator sends compensating commands to undo the effects of the previous steps. Here’s an example of an Orchestrated Saga for a flight booking scenario:

- Reserve a flight

- Reserve a car rental

- Process payment

- Confirm payment

- Confirm car rental

- Confirm flight

If any of the steps fail, the orchestrator can execute compensating actions to undo the effects of the previous steps. For example, if the payment fails, the orchestrator can send a command to cancel the car rental and flight reservations.

Choreography Saga

In a Choreography Saga, there is no central orchestrator. Instead, each service communicates directly with the other services involved in the transaction. Each service knows its own responsibilities and the events it should listen for from other services. If a step fails, each service can execute compensating actions to undo the effects of its own steps. Here’s an example of a Choreography Saga for a flight booking scenario:

- Reserve a flight and send an event to the payment service

- Reserve a car rental and send an event to the payment service

- Process payment and send an event to the flight and car rental services

- Confirm payment and send an event to the flight and car rental services

- Confirm car rental and send an event to the flight service

- Confirm flight

If any of the steps fail, the services can execute compensating actions to undo the effects of their own steps. For example, if the payment fails, the payment service can send events to cancel the flight and car rental reservations.

Implement Saga Pattern using AWS Step Functions

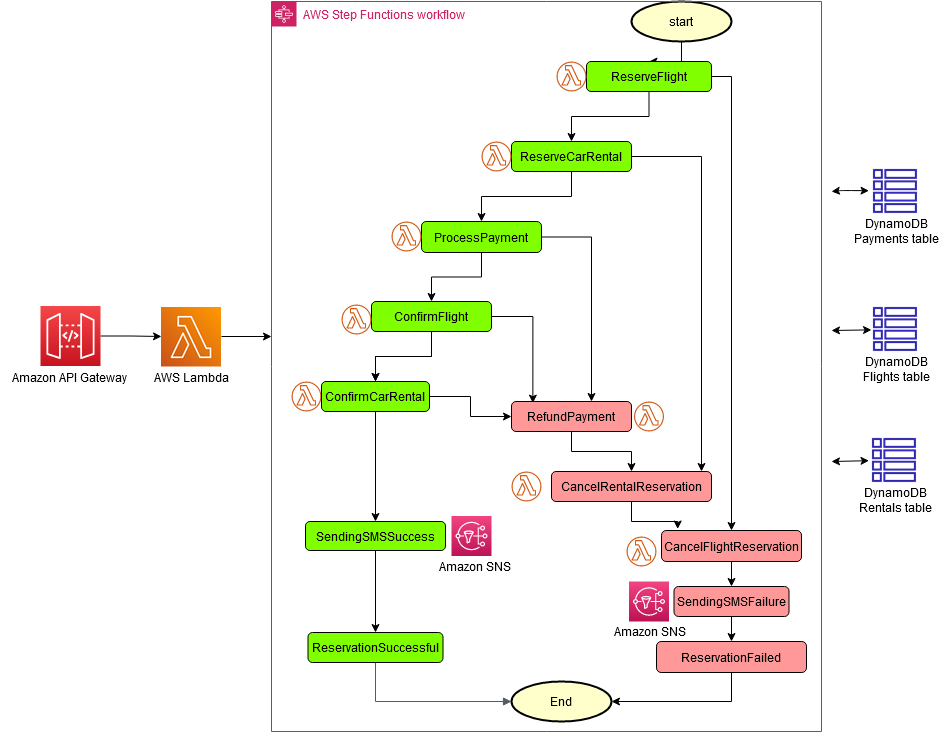

Implementing saga using AWS Step Functions is a powerful tool for coordinating microservices in a distributed system. In this scenario, we will explore how AWS Step Functions can be used to implement a saga for a flight booking process, which involves reserving a flight, reserving a car rental, processing payment, and confirming the bookings.

The saga begins with a reserveFlight step, which initiates the flight booking process. Once the flight reservation is complete, the saga moves on to the reserveCarRental step to reserve a car rental for the same trip. If the car rental reservation fails, the saga should roll back the previous step and cancel the flight reservation.

Next, the processingPayment step processes the payment for the reservations. If payment processing fails, the saga should roll back both the flight and car rental reservations.

After payment processing is successful, the confirmPayment step confirms the payment and moves on to the confirmCarRental step to confirm the car rental reservation. If the confirmation fails, the saga should roll back both the payment and car rental reservations.

Finally, the confirmFlight step confirms the flight reservation. If the confirmation fails, the saga should roll back the payment, car rental, and flight reservations.

AWS Step Functions provide a powerful toolset for coordinating these steps in a distributed system. The state machine can track the progress of the saga and roll back steps as needed. Additionally, AWS Step Functions support complex branching logic, allowing the saga to make decisions based on the results of each step.

References

- O’Reilly - Building Microservices, 2nd Edition (Chapter 6: Workflow)

- Manning Publication - Microservices Patterns With examples in Java (Chapter 4: Managing Transactions with Sagas)

- Microservice Architecture - Pattern: Saga

- Saga distributed transactions pattern

- Example: Saga transaction with compensation

- Saga pattern in AWS

- Implement the serverless saga pattern by using AWS Step Functions

- Building a serverless distributed application using a saga orchestration pattern

- Saga Pattern: Misconceptions and Serverless Solution on AWS