Concurrency plays a crucial role in developing efficient and responsive Java applications. Understanding the fundamentals of Java concurrent programming is essential for writing robust and scalable code. In this blog post, we’ll explore several key aspects of Java concurrent programming, including the lifecycle of a Java thread, different methods to create a Java thread, inter-thread communication, mechanisms for thread safety.

1. Lifecycle of Java Thread

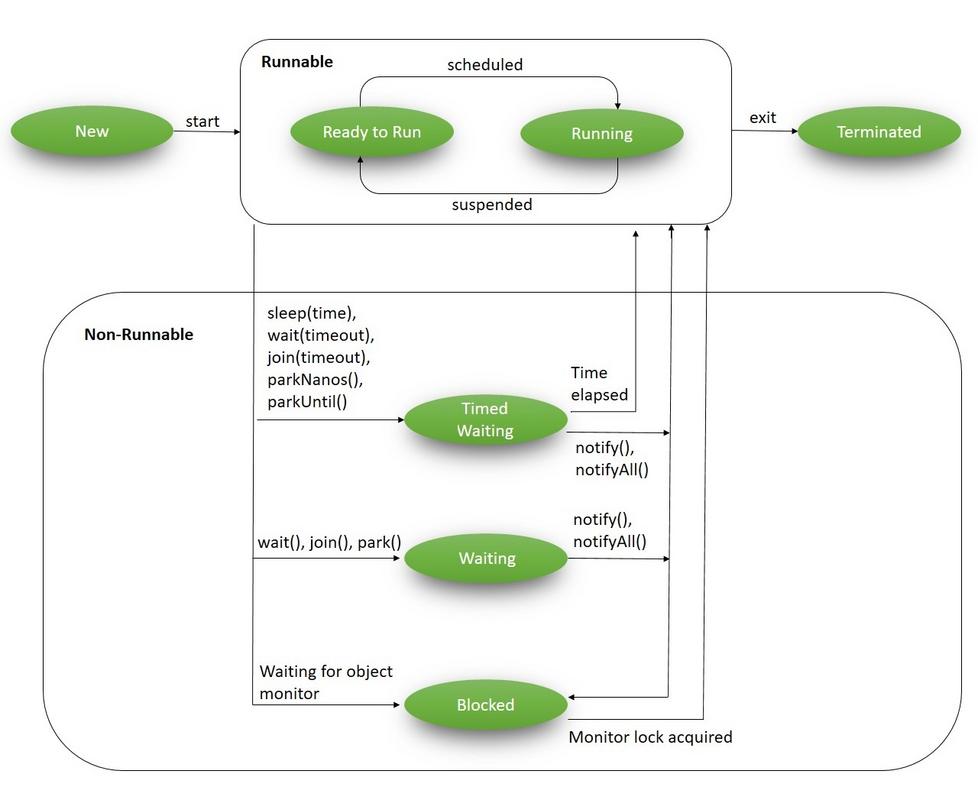

A Java thread has a well-defined lifecycle, consisting of the following states:

NEW:** The thread is in this state before it is started. Note:start()method has not been invoked yet.RUNNABLE:** The thread is ready to run, and it can be scheduled by the Java Virtual Machine (JVM).RUNNING:** The thread is currently executing its code.BLOCKED:** The thread is temporarily inactive and cannot proceed until a certain condition is satisfied.WAITING:** The thread is waiting for other threads action, without time limitTIME_WATITINGThe thread is waiting for a specific period of time.TERMINATED:** The thread has completed its execution or has been stopped.

Source: https://www.baeldung.com/java-thread-lifecycle

2. Different Methods to Create Java Thread

Java provides several methods to create and start threads, each with its own advantages and use cases. Let’s explore four commonly used methods:

2.1 Extending the Thread class

In this approach, you can create a new class by extending the Thread class and overriding its run() method. The run() method contains the code that will be executed by the thread when started. Here’s an example:

public class MyThread extends Thread {

@Override

public void run() {

// Thread's behavior goes here

}

}

// Creating and starting the thread

MyThread thread = new MyThread();

thread.start();

Pros:

This method allows you to directly work with the Thread class and provides flexibility in defining the behavior of the thread.

Cons:

In Java, a class can only inherit one parent class. In this case, any resource class that could potentially be improved by Concurrency need to extends Thread class, which add the limitation to extends other business related classes.

2.2 Implementing the Runnable interface

Another way to create a thread is by implementing the Runnable interface. This approach separates the thread’s behavior from the Thread class, promoting better separation of concerns. Here’s an example:

public class MyRunnable implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

// Thread's behavior goes here

}

}

// Creating and starting the thread

Thread thread = new Thread(new MyRunnable());

thread.start();

By implementing Runnable interface, you can reuse the same instance of the behavior in multiple threads, enhancing code modularity.

2.3 Using the ExecutorService framework (ThreadPool)

The ExecutorService framework provides a higher-level abstraction for managing and executing threads. It handles the creation, pooling, and lifecycle management of threads, allowing you to focus on the tasks to be executed. Here’s an example:

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(5);

// 1) Executing a task

// execute() method take in a instance that implement Runnable interface

executor.execute(new ERunnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

// Thread's behavior goes here

}

})

// 2) Submitting a task to the executor for execution

Future<Object> future = executor.submit(taskWithReturnValue);

// Shutting down the executor after tasks are completed

executor.shutdown();

The ExecutorService framework provides more control over thread execution, thread pooling, and handling the returned results of the executed tasks. This is the most common way to implement a Java Concurrent program, we will dive deep more into this ExecutorService framework in a dedicated article.

2.4 Implementing the Callable interface**

The Callable interface is similar to Runnable, but it allows threads to return a result or throw checked exceptions. It is commonly used when you need to perform a task and obtain the result asynchronously. Here’s an example:

Callable<String> task = () -> {

// Thread's behavior goes here

return "Task completed successfully";

};

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor();

// Submitting the task to the executor and obtaining a Future

Future<String> future = executor.submit(task);

// Getting the result from the Future

try {

String result = future.get();

System.out.println(result);

} catch (InterruptedException | ExecutionException e) {

// Handle exception

}

// Shutting down the executor after the task is completed

executor.shutdown();

The Callable interface provides a way to perform tasks in a separate thread and obtain their results asynchronously.

These different methods to create Java threads provide flexibility and cater to various threading scenarios. Choosing the appropriate method depends on factors such as code structure, behavior reusability, thread management, and the need for returned results.

3. Inter-Thread Communication

Inter-thread communication allows threads to synchronize and communicate with each other, enabling coordinated execution and data sharing in multithreaded applications. Java provides several mechanisms for inter-thread communication. Let’s explore two commonly used methods:

3.1 Using wait() and notify() methods

The wait() and notify() methods are defined in the Object class and are used for basic inter-thread communication. Threads can use these methods to wait for a condition to be satisfied and notify other threads when the condition changes. Here’s an example:

// Shared object for communication

Object sharedObject = new Object();

// Thread 1 (waiting)

synchronized (sharedObject) {

while (!condition) {

try {

sharedObject.wait(); // Thread 1 waits until notified

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// Handle exception

}

}

}

// Thread 2 (notifying)

synchronized (sharedObject) {

// Change the condition

condition = true;

sharedObject.notify(); // Thread 1 is notified and resumes execution

}

In this example, Thread 1 waits until the condition is satisfied and releases the lock on the shared object using wait(). Thread 2 changes the condition and notifies the waiting thread using notify(), allowing Thread 1 to resume execution.

3.2 Using BlockingQueue

The BlockingQueue interface, available in the java.util.concurrent package, provides a higher-level mechanism for inter-thread communication. It offers thread-safe operations for adding, removing, and retrieving elements from a queue, blocking the calling thread if necessary. Here’s an example using LinkedBlockingQueue:

BlockingQueue<String> queue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>();

// Thread 1 (waiting)

try {

String item = queue.take(); // Thread 1 blocks until an item is available

// Process the item

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// Handle exception

}

// Thread 2 (adding)

try {

queue.put("Item"); // Thread 2 adds an item to the queue

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// Handle exception

}

In this example, Thread 1 blocks at queue.take() until an item is available in the queue. Thread 2 adds an item to the queue using queue.put(), potentially unblocking Thread 1 and allowing it to retrieve and process the item.

Using BlockingQueue simplifies thread coordination by providing a built-in blocking mechanism and reducing the need for explicit synchronization.

These are just two common methods for inter-thread communication in Java. Other mechanisms like CountDownLatch, CyclicBarrier, and Semaphore can also be used based on specific requirements.

By leveraging inter-thread communication, you can ensure proper synchronization, avoid race conditions, and facilitate collaboration between threads in a multithreaded environment.

4. Mechanisms for Thread Safety

Ensuring thread safety is crucial in multithreaded applications where multiple threads access shared resources concurrently. Java offers various mechanisms to achieve thread safety. Let’s delve into some commonly used ones in more detail:

4.1 Synchronization using the synchronized keyword

The synchronized keyword is a fundamental mechanism for achieving thread safety in Java. It allows you to create synchronized blocks or methods to ensure exclusive access to shared resources. By acquiring an intrinsic lock, also known as a monitor, only one thread can execute the synchronized code block or method at any given time. This prevents multiple threads from concurrently modifying shared data and ensures thread safety. However, it can introduce performance overhead due to the need for acquiring and releasing locks. Here’s an example:

public class Counter {

private int count;

public synchronized void increment() {

count++;

}

}

In this example, the increment() method is synchronized, guaranteeing that only one thread can execute it at a time. Synchronization protects the integrity of shared data by preventing race conditions and ensuring thread-safe access to the count variable.

4.2 Use of the volatile keyword

The volatile keyword ensures that changes to a variable are immediately visible to other threads. It provides a lightweight synchronization mechanism that ensures proper visibility but does not provide atomicity for compound actions. When a variable is declared as volatile, reads and writes to that variable are directly performed on the main memory, bypassing thread-local caches. This guarantees that the most up-to-date value of the variable is always accessed by all threads. Here’s an example:

public class SharedData {

private volatile int value;

public void updateValue(int newValue) {

value = newValue;

}

}

In this example, the volatile keyword ensures that updates to the value variable are immediately visible to other threads. It helps in achieving thread safety when the variable is shared among multiple threads.

4.3 Utilizing thread-safe data structures

Java provides a range of thread-safe data structures in the java.util.concurrent package, designed specifically for concurrent access without the need for external synchronization. These data structures, such as ConcurrentHashMap, CopyOnWriteArrayList, and ConcurrentLinkedQueue, offer built-in thread safety and handle synchronization internally. They employ various techniques like lock striping, non-blocking algorithms, or fine-grained locking to allow multiple threads to access and modify the data concurrently. Here’s an example:

ConcurrentHashMap<String, Integer> map = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

// Thread-safe operations on the ConcurrentHashMap

map.put("key", 10);

int value = map.get("key");

By utilizing thread-safe data structures, you can avoid the complexities of explicit synchronization while ensuring thread-safe access to shared data. These structures are designed to handle concurrent modifications efficiently and maintain data consistency.

4.4 Atomic classes from java.util.concurrent.atomic

The java.util.concurrent.atomic package provides atomic classes that facilitate atomic operations on shared variables without the need for explicit synchronization. Atomic classes, such as AtomicInteger, AtomicLong, and AtomicReference, offer methods that perform operations atomically, ensuring thread safety. Under the hood, atomic classes use low-level CPU instructions or compare-and-swap (CAS) operations to achieve atomicity. Here’s an example:

AtomicInteger counter = new AtomicInteger();

counter.incrementAndGet();

In this example, the incrementAndGet() method of AtomicInteger increments the value atomically without the need for external synchronization. Atomic classes are highly efficient and are particularly useful when multiple threads need to perform operations on shared variables concurrently.

These mechanisms, along with other advanced techniques like locks, semaphores, and condition variables, aid in achieving thread safety in Java applications. It’s important to choose the appropriate mechanism based on factors such as performance, granularity of synchronization, and the specific requirements of your application.

5. Real-World Java Code Example

To demonstrate the concepts of concurrent programming in Java, let’s consider a real-world scenario of a ticket-selling system. In this example, multiple threads will simulate ticket buyers attempting to purchase tickets concurrently. We’ll ensure thread safety using synchronization. Here’s the code example:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class TicketCounter {

private int availableTickets;

private final Lock lock;

public TicketCounter(int availableTickets) {

this.availableTickets = availableTickets;

this.lock = new ReentrantLock();

}

public void sellTickets(int requestedTickets) {

lock.lock(); // Acquire the lock

try {

if (availableTickets >= requestedTickets) {

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " purchased " + requestedTickets + " tickets.");

availableTickets -= requestedTickets;

} else {

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " attempted to purchase " + requestedTickets +

" tickets but there are only " + availableTickets + " tickets available.");

}

} finally {

lock.unlock(); // Release the lock

}

}

}

public class TicketBuyer implements Runnable {

private final TicketCounter ticketCounter;

private final int requestedTickets;

public TicketBuyer(TicketCounter ticketCounter, int requestedTickets) {

this.ticketCounter = ticketCounter;

this.requestedTickets = requestedTickets;

}

@Override

public void run() {

ticketCounter.sellTickets(requestedTickets);

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

TicketCounter ticketCounter = new TicketCounter(100);

// Creating multiple threads representing ticket buyers

Thread buyer1 = new Thread(new TicketBuyer(ticketCounter, 5));

Thread buyer2 = new Thread(new TicketBuyer(ticketCounter, 10));

Thread buyer3 = new Thread(new TicketBuyer(ticketCounter, 8));

// Starting the threads

buyer1.start();

buyer2.start();

buyer3.start();

}

}

In this example, we have a TicketCounter class that simulates a ticket counter with a specified number of available tickets. The sellTickets() method is synchronized using a Lock object (ReentrantLock) to ensure thread safety.

The TicketBuyer class represents a ticket buyer and implements the Runnable interface. Each buyer attempts to purchase a certain number of tickets by invoking the sellTickets() method of the TicketCounter instance.

In the Main class, we create multiple threads (buyer1, buyer2, buyer3) representing different ticket buyers. Each thread attempts to purchase a specific number of tickets by calling the run() method.

When executing the code, the threads will concurrently attempt to purchase tickets. The Lock object ensures that only one thread can access the shared TicketCounter object at a time. This guarantees thread safety and prevents multiple buyers from purchasing the same ticket.

Conclusion

Understanding the fundamentals of Java concurrent programming is crucial for writing high-performance and scalable applications. By grasping the lifecycle of Java threads, different methods to create threads, inter-thread communication, mechanisms for thread safety, and exploring real-world code examples, you are well-equipped to develop concurrent Java applications effectively.

By following best practices and utilizing the appropriate techniques, you can harness the power of concurrency and unlock the potential of your Java programs.